|

Make your own

Traditional Wooden Skis

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

I had never been skiing before or even held a pair of skis, but making a

pair seemed like a fun idea! Even in England where snow may only be

around for a few days of the year, the fun that can be had on those days

makes the effort in making them well worth while! This article shows how

I made mine.

My imagination was first sparked when watching a Swedish film about

native Reindeer herders. For such people skis are not all about fun and

high speed downward slopes, in northern climates skis provide a means of

moving across the top of deep snow which can potentially be meters

thick. Without such equipment as skis or snowshoes, travel across the

landscape would be incredibly difficult.

Unlike most modern skis, traditional

wooden skis like those which were made by our ancestors can vary hugely

in size. It's wise to make skis according to how and where they'll be

used. A large surface area is better suited for situations where snow is

very deep and powdery. In Siberia the natives made skis which could

exceed a width of 12 inches each! On well used ski runs where the

snow is more compacted, narrow skis can be used for more speed.

One of the first things I learnt about skis

is that generally they are not just flat pieces

of wood with a bend at the end, they are also bent

from one end to the other meaning that when not in use the centre of the ski will stand off the

ground slightly. This bend serves to spread the weight

of the user more evenly over thick snow; Instead of the centres dipping down the skis

just become flat.

|

|

| |

picture showing an overall bend in the ski, see how it

stands away from the ground slightly at the centre. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

For my timber I was lucky enough to find a trunk of Ash wood

left by loggers on a fire heap, as a bonus the log was

also naturally bent along it's length, this was perfect, I could utilise

this natural shape the achieve the overall bend as explained above.

Scandinavians generally used Hardwoods for skis, typically

Ash or Birch, but also favoured pitch saturated Pine. In Norway it is

apparently true that if you died whilst using skis made of Elm you were

not to be buried on holy ground

since it was considered suicide because they were so slippery! Siberian

tribes frequently used Softwoods like Spruce, Pine or Larch. It's worth

noting that the Siberians nearly always lined the undersides of their

skis with leg skins (of any large animals), this would prevent the

softwoods from weaving out. Also, the flow of fur was aligned backwards

to give excellent traction when moving uphill.

The timber you choose should have as few knots and side branches

as possible. Also the grain needs to be straight and not twisted; you don't want

to split the log in half and it look like a propeller... You can usually

tell if the grain is twisted in a tree by studying the bark.

In a log of timber the sections of wood to be used will be

different according to whether you are using hardwood or Softwood. For

hardwoods have the growth rings aligned 'parallel' with the width of the

ski (see fig 1). For a softwood have the growth rings vertically

aligned (perpendicular) (fig 2). |

|

| |

fig 1 |

|

fig 2 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

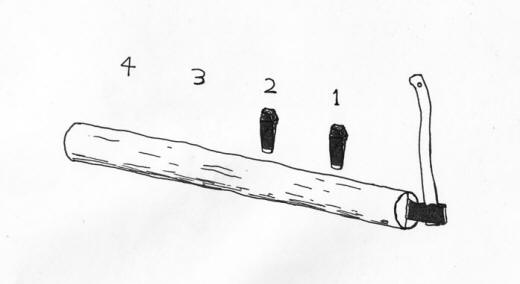

If the skis are to be made the traditional way the log

should to be split into workable staves using wedges. The diameter of

the log will determine how many times it can be split down to

result in workable pieces. The log I used was fairly thick so I could

afford to split it into quarters. Carefully inspect the wood beforehand to Plan where best to make

the split to account for any natural quirks.

I Start with a felling axe, using a sledge hammer I

tap it into the end of the log until the wood begins to split. Then I

place a wedge into the split and hammer it. As the split opens further

the axe will loosen and can be taken out. We now just use

wedges to do the rest. Hammer a second wedge into the split slightly ahead of the

first. The first wedge will then loosen and this can be moved ahead even

further. The wedges are moved one after the other until the other end is

reached and the log falls into two halves. If you're lucky this will

have been as straight forward as it sounds and the split will have run

in a straight line. If the split had run off to one side at any point

the next wedge would need to be hammered in further ahead and off to one

side to encourage the split back to the middle.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

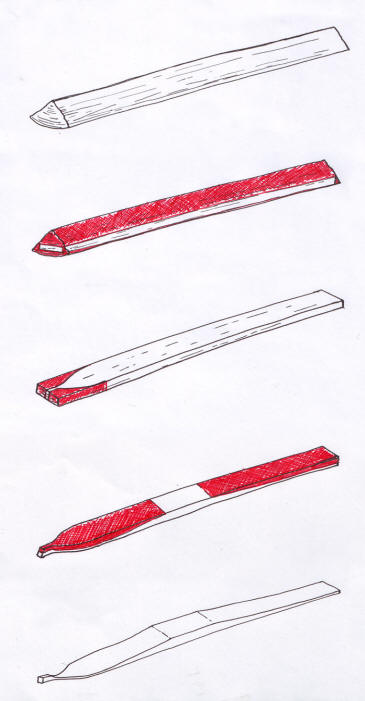

Shaping the woodThe following

shows my strategy for reducing a quarter

log of Ash wood into a ski. (red indicates wood to be be removed.

Drawings not to scale)

|

|

| |

|

|

| This job will be a lot

easier if completed while the wood is still green.

Firstly the bark is stripped using a regular knife or

draw knife. The rough stave then needs to be reduced to

a regular plank with dimensions to accommodate the

widest and thickest parts of the finished ski. At the

beginning you'll need to remove large amounts of wood,

this can be done by making a series of saw cuts a few

inches apart along the stave, blocks of wood can then be

split away with the axe, chopping through from one saw

cut to the next... (Be careful not to make the initial

saw cuts too deep otherwise you'll be left with wood only

suitable for the fire!). The plank is then hewn with an

axe to refine the shape and surface, a drawknife and

shave horse would also work perfectly. A chalk plumb

line is a handy piece of kit for marking straight lines

to use as guides. |

| |

The profile of the ski front is now drawn on and shaped with a

combination of axe and knife. |

| |

| |

| |

A middle section where

your foot is to be placed remains a regular thickness

and the wood tapered away either side down to either

end. |

|

A plane, farriers rasp and a cabinet scraper are also

excellent tools for refining the shape down to final

dimensions. |

| |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

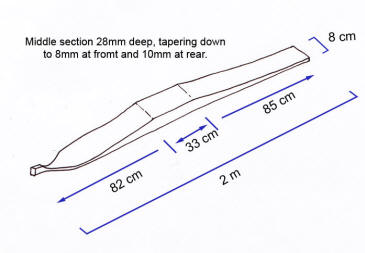

It's up to you to

decide on the dimensions of your own skis, but for reference here's

how mine measure up.

(Notice how a small nodule of wood has been left at the front which

can be carved into a decorative end piece later on.)

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Skis now ready

for steam bending the ends... (Notice how I also shaped the rear

ends a little too; just to take the corners off.) |

|

To create the

overall bend in the skis (as explained earlier) the wood can be

strapped to a straight plank and propped open at the centres. As the

wood seasons the

skis will take on this shape, this will only work if the wood is still

green. You may consider propping the wood further out than is

pictured as the wood will settle somewhat when unstrapped.

Note: It is

best to steam bend the ski ends while the wood is still green, so

you can return the skis to this form later after steaming, then

leave until fully seasoned.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Steam bending the ends |

|

| |

|

To steam bend the

ends I wrapped the wood in hessian material from an old sack, I then soaked

this with water and wrapped the the lot with

turkey aluminium foil. I then supported this

over a hot fire for perhaps 45 minutes

(note how a log shields the unprotected wood

from the heat. The pieces of wood on top of the

foil are just weighing a flap down). |

|

|

| |

|

Before steaming I had already rigged up some cord which

would enable me to swiftly make the bends and

hold them in shape. A small loop was tied to the tip and

a separate long length secured at the centre of the

ski. When the wood had been steamed for long

enough, I could then quickly unwrap the wood,

thread the long cord through the small loop at the end, then

pull down with force to bend

and hold the wood in shape.

Note:

the hole

drilled through the ski towards the front of the middle

section (where the cord is tied) will later be chiselled out

into a wider slot through which the foot bindings can be

attached. It is important to note that this point is

forward of the true centre so that in use the ski will be slightly back heavy, this is so

that when your

foot is lifted the front of the ski will rise first.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Last stages to be completed:

- Chiselling out a rectangular slot hole through

which I could secure the bindings

- Carving the decorative ends in a traditional

Swedish style

- All surfaces

are given a coat of pure Pine tar to help prevent snow sticking

to the wood. As the tar is brushed on it is heated with a blow torch

to help it go into the wood. Excess tar is rubbed off with a rag.

(Tar made by 'Bickmores', marketed as a horse hoof treatment.

Purchased off the internet).

- Applying Bees wax to the undersides to make the

skis glide better, I simply rubbed it on like a

crayon and whipped over it with the blowtorch to even it out.

Special ski wax can be purchased which will last much longer. I

found that without the wax snow

would clog up the skis (in colder climates where

the temperature is much lower and the snow more powdery, this

problem would not occur, just the Pine tar treatment would

likely be enough).

- Finally I had to make the

foot bindings. Again I decided to make these in the traditional

way from withies, which are long thin shoots of fresh or soaked

wood twisted lengthways until the fibres separate, creating

flexible, strong rope-like strands. I used Willow, but Birch

shoots were commonly used. I could not find any instructions on

how to make/ assemble these so a little improvisation was

needed. They had to be a tight fit so I formed them around my

boot while fitting them.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Decorative

carved ends |

|

Willow

'withies' as bindings. Several strands wrapped together to make a

strong rope-like structure. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Put to the test... |

|

| |

|

|

| |

This

was my first time using any pair of skis, I'm a total beginner so

with nothing to compare against I can't give a conclusive review of

their performance. However they did seem to work pretty well and

sure put a smile on my face! Since the snow was not very deep I

could just use a couple of suitably straight sticks as ski poles.

After a fair few runs my Willow withy bindings have loosened, so

I'll be replacing these with some thick leather straps complete with

buckles to really get things secure. This will give better control

of direction too.I hope

this article has inspired you to have a go at making your own...

Stay safe and have fun!

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|